Mastodon, quote boosts, dread, and the science fiction of A. Bertram Chandler

(The above is what's called, in Mastodon land, a "CW", which used to mean "content warning" but is now often referred to as a "content wrapper": i.e., the subject line. You have been warned, or wrapped, about what I will now subject you to.)

Background

There is a heated debate on Mastodon about whether the software should support the "quote tweets" of Twitter. Mastodon, so I'm told, was created by and for marginalized (especially sexual/gender minority) groups that fled from the hostility of Twitter, and they saw the quote tweet as an amplifier for that hostility, because it makes it so easy and tempting to quote someone's tweet with a dismissive/insulting comment: "dunking on". When people with a lot of followers do that, it can lead to "piling on", where the "influencer" encourages the followers to verbally attack the writer of the original tweet. That can escalate into real-world harassment and danger.

So, while the dominant Mastodon software has an equivalent to retweeting (called "boosting"), it doesn't have a one-click quote tweet equivalent. You can still write your comment and paste a link to the original post, but the link isn't expanded inline, so the affordance is very different. The effect is as desired: people don't discuss other people's tweets, they respond to them.

Pretty much everyone agrees that sometimes discussions are better than responses. I myself often quote tweet on Twitter as a way of amplifying someone else's tweet with a bit of commentary (often a line or two about why my particular followers might find it useful). So I miss having quote tweets for that.

On the other hand, I do not miss the temptation to dunk on people. When I came to Mastodon and encountered the reason for it not having quote boosts, I did realize that quote tweets had encouraged me to be nastier than I really think I ought to be, and I resolved to generally be a more pleasant person on Mastodon than I had been on Twitter. More of a "yes, and" person than a "no, because" person, and especially than a "no, because you're stupid and/or evil" person.

On the gripping hand, there exist Twitter communities, most notably #BlackTwitter, that use quote tweets as an integral part of their subculture, and they miss it. #BlackTwitter's introduction to Mastodon was rocky for another reason: those habituated to existing Mastodon etiquette would tell them to place discussions of racism behind content warnings, to which the #BlackTwitter diaspora reacted by saying, "What, you want me to put the central fact of my whole life behind a content warning, just to avoid a little discomfort on your part?" The quote boost issue seems, to me, have made a rocky start even worse.

As if it mattered...

...my own opinion today is, roughly, "Don't just do something, sit there." Everyone agrees (but see below) that making a safe/welcoming/whatever environment is an interplay of technology, social norms, and social behavior (moderation, scolding, etc.) Given that the population of Mastodon is changing so much, so fast, the "tone" and norms are bound to change, at least somewhat. It seems to me simpler to let that one big change play out before deciding on new technology.

But note that I have no skin in the game: quote tweets just weren't as important to my Twitter experience as they were to others. So of course I'm OK with going slow; it's not me that's had a hole blown in my community.

Dread

For the past week or so, I've been captured by a weird feeling whenever quote boosts get mentioned: a combination of dread, sadness, and inevitability. And an exasperating sense that I could almost remember reading something, long ago, that captured that feeling.

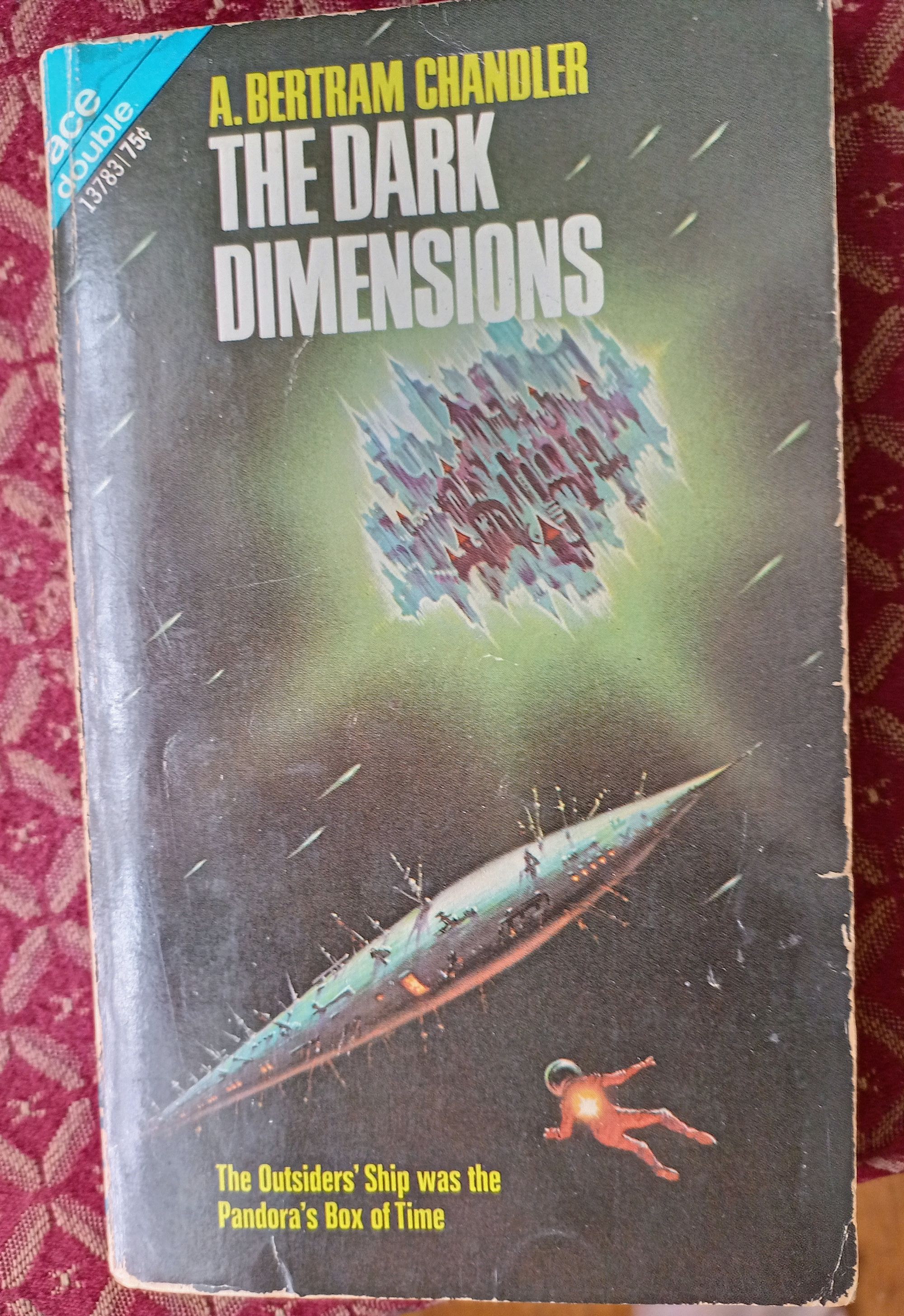

Finally, last night, I really remembered the source. A bit from A. Bertram Chandler's /The Dark Dimensions/ (1971), which I read in an Ace Double edition (so, about the time it came out, when I was 12), and which I happen to still have:

First, Chandler's dread

In the book, the protagonist, Grimes, is a captain of a space ship near the edge of the galaxy. There is a mysterious object there, called the Outsider, that's swallowed up earlier expeditions without a trace. Grimes is part of yet another attempt. It turns out that characters from other authors' fictional universes are, at the same time, on their own expeditions with the same purpose. (Grimes knows, but does not fully believe, that he's a fictional character. In one story, he meets his own author.) Conflict happens.

Toward the end, Grimes enters the Outsider and begins to search, and something takes over:

Grimes hesistated only briefly, then began to stride along the alleyway. Sonya stayed at his side. The others followed. Consciously or unconsciously they fell into step. The regular crash of their boots on the metal floor was echoed, reechoed, amplified. They could have been a regiment of the Brigade of Guards, or of Roman legionaries. They marched on and on, along that tunnel with no end. And as they marched the ghosts of those who had been there before kept pace with them – the spirits of men and of not-men, from only yesterday and from ages before the Terran killer ape realized that an antelope humerus made an effective tool for murder.

It was wrong to march, Grimes dimly realized. It was wrong to tramp into this... temple in military formation, keeping military step. But millenia of martial tradition were too strong for him, were too strong for the others to resist (even if they wanted to do so). They were Men, uniformed men, members of a crew, proud of their uniforms, their weapons and their ability to use them. Before them – unseen, unheard, but almost tangible – marched the phalanxes of Alexander, Napolean's infantry, Rommel's Afrika Corps. Behind them marched the armies yet to come.

Damn it all thought Grimes desperately, we're spacemen, not soldiers. Even Dalzell and his Pongoes are more spacemen than soldiers.

But a gun doesn't worry about the color of the uniform of the man who fires it.

"Stop!" Mayhew was shouting urgently. "Stop!" He caught Grimes' swinging right arm, dragged on it.

Grimes stopped. Those behind him stopped in a milling huddle – but the hypnotic spell of marching feet, of phantom drum and fife and bugle, was broken.

Whew! Spell broken! But it turns out another group has entered the Outsider, intent on taking out Grimes' group:

"Down!" barked Dalzell, falling prone with a clatter. The others followed suit. There were dim figures visible at the end of the tunnel, dim and very distant. There was the faraway clatter of some automatic projectile weapon. The Major and his men were firing back, but without apparent success.

And at the back of Grimes' mind a voice – an inhuman voice, mechanical but with a hint of emotion – was saying, No, no. Not again. They must learn. They must learn.

Then there was nothingness.

Spoiler: they – humanity – doesn't learn. Not this time. If I remember correctly, Grimes' universe sort of gets restored from backup. The end.

Next, my dread

My dread is that the quote boost debate has succumbed to the same nigh-irrestible desire to find an enemy to vanquish. I don't directly follow the debate, but I frequently have it boosted into my timeline by people I do follow. Because I'm one of the Twitter diaspora, I mainly see the posts of the people really mad that the long-time Mastodon users are not listening, instead clinging to their position of white privilege (with special ire for white women) and nonsensically claiming, in their tech-bro way, that technology will solve social problems. (Despite, as far as I can tell, nobody claiming that.)

As I say, it's mostly one side of the debate that gets boosted into my awareness. My impression is that the anti-quote-boost side is just as enthusiastic about Othering. (After all, a flood of newbies practically cries out to be othered as destructive tourists invading a peaceful town.)

From my privileged and not-as-informed-as-I-probably-should-be vantage point, it looks like two disadvantaged minorities (one grouped by sexuality or minority gender, one grouped by race and minority culture) fighting bitterly while straight white guys like me look on, unaffected by the results. And they're fighting in the old old ways, captured by "the hypnotic spell of marching feet, of phantom drum and fife and bugle" – the hypnotic spell of having an enemy who is inherently wrong.

No, no. Not again. They must learn. They must learn.

But probably not this time.

That trick never works

I guess I'll end with a go-to quote for the straight white male liberal who can be comfortable looking on with alarm.

Rodney King, heartbroken during the 1992 Los Angelos riots: "I just wanna say, you know, can we all get along? Can we get along? Um, can we stop making it... making it horrible for the older people and the kids?"